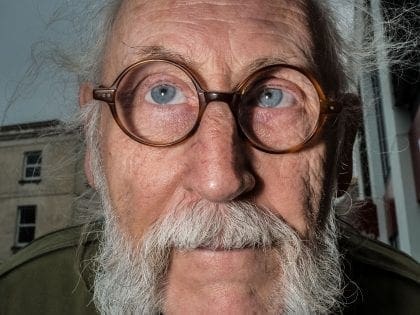

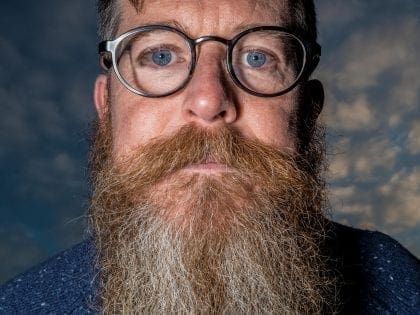

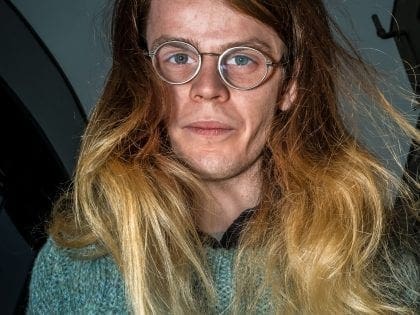

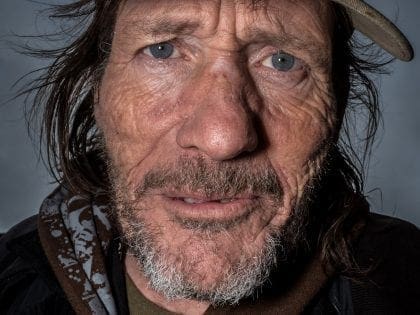

What began as a social media project for British creative director Marksteen Adamson, soon evolved into a social study set in his hometown of Cheltenham. Armed with a small Leica camera, Adamson would take every opportunity, journeying to and from his studio, to capture portraits of people he would see and meet in the streets where he lives and works.

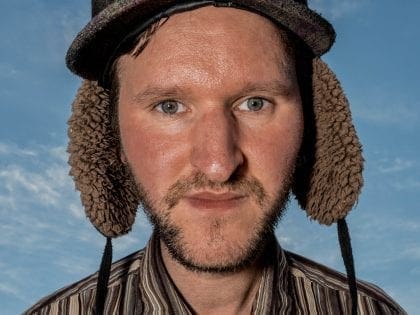

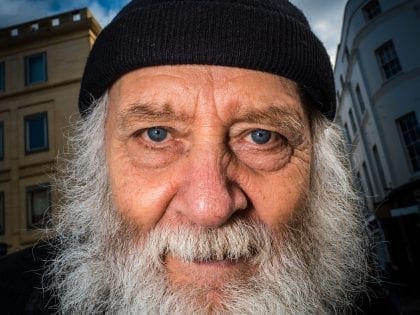

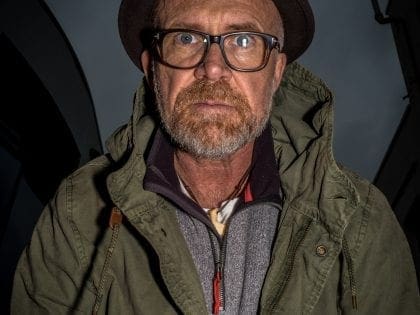

At first glance, the close-up street portraits by the self-taught photographer, Marksteen Adamson, could be reminiscent of Bruce Gilden’s wide-angled distorted faces, or Martin Parr’s ‘stolen moments’. Adamson acknowledges both Gilden and Parr as sources of inspiration. His approach however, differs from the two icons of socio-documentary street photography as he explains: “It’s easy to find people who are broken and to photograph them. It’s more dramatic but, I think, less respectful to the subject.”

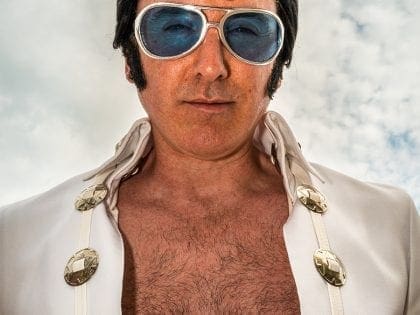

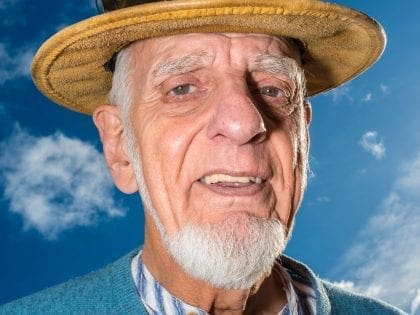

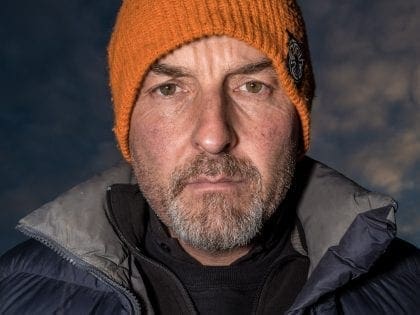

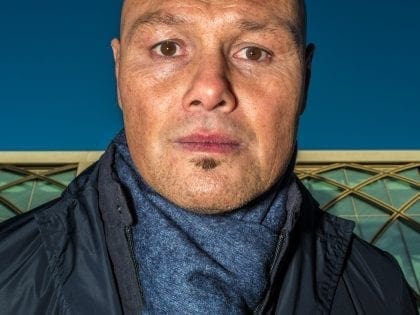

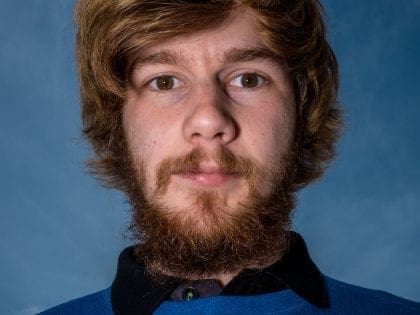

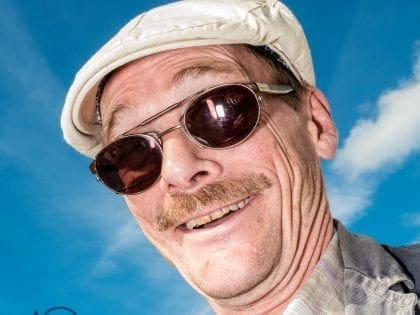

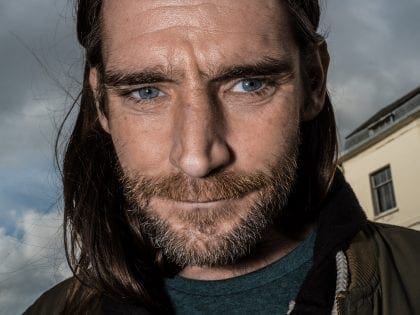

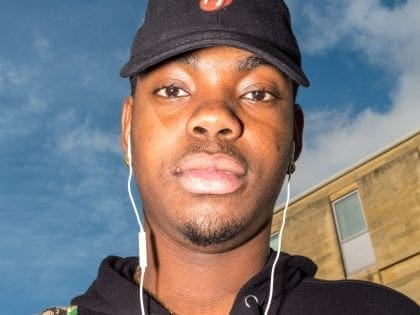

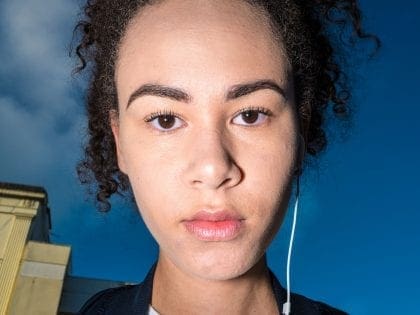

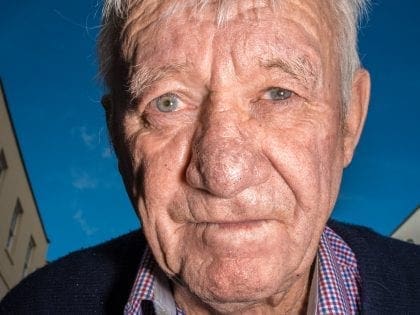

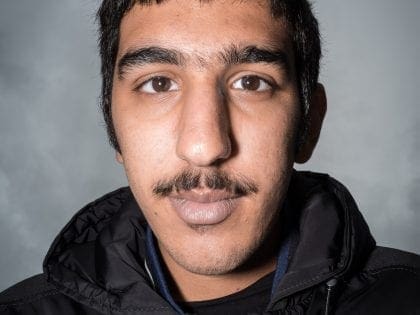

With his Cheltenham Folk portrait series, Adamson’s goal is to produce a balanced reportage of his hometown. Rather like a social study of a town that is primarily known in the UK as the location of GCHQ, the Government Communication Headquarters, the heartland of horse racing, and home to members of the upper classes. These perceived images do not align however with Adamson’s impression of the town: “Cheltenham has a massive variety of people, culturally, economically and socially, the town contains the whole spectrum.”

Raised in Tanzania and having lived and worked around the world, Adamson took time to adjust to the fact that the UK can be very grey and dull most of the year, but as he was now settled here, he decided to start photographing local people in the street in his free time. He started to realise that Cheltenham is full of really interesting people and not as monochromatic as he’d thought for so many years.

“I want to show the beauty and character in each person I meet. There is something special about everyone regardless of who they are. Some have stories to tell and others are in a hurry. Some of them are homeless, some are wealthy, some are more educated than others, but most of them are just ordinary, everyday, working people.”

He also knows about the temptation of selecting images where those portrayed are not shown in the best light. “Sometimes I have to be strong and resist publishing a picture where the person appears somewhat ridiculous. The image might prove more compelling, but it would be lacking in compassion.”

Over a number of years, the creative director had become bored with photography. Then, two and a half years ago, he bought a Leica camera and challenged himself to do the hardest thing he could imagine – street photography. Soon, Adamson wanted to get even closer to his subject, but without ‘stealing their image’ as some street photographers do. Conversely, he decided to address his fellow citizens directly, despite the risk of rejection that entails. “You have to be emotionally prepared for them to say no. It’s not easy to be rejected and it sometimes affects me, but I have to remind myself that it’s not because of me, but more about them not wanting to be photographed.” It is, of course, natural for people to adjust their expression if they know they are being photographed, however, Adamson has a technique for getting around this problem: “If I take 15 to 20 pictures of the same person quickly, there will always be one shot where they are not really posing, and then I’m able to capture something unique about them.” After taking the photograph, he asks the person for their first name and uses just that as the title for the portrait, he then posts it on Instagram. He has made a conscious decision not to write down the person’s story – he is not aiming to produce a project like Brandon Stanton’s Humans of New York, rather, he wants to leave room for interpretations and projections. In this manner, each viewer can ask his or her own questions about the lives of those portrayed.

For his Cheltenham Folk series Adamson learned how to use a flash in daylight. Because he did not want to rely on the camera’s automatic programme settings, he controlled the light with manual settings. “It’s tough to use the flash appropriately, because the proximity and the surrounding light change the impact it has,” he explains. Adamson spent long hours practising until he found the right setting. He has even gone so far as to fix the flash with tape, so the setting will not accidentally be changed.

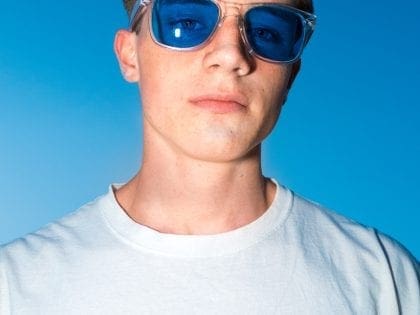

“The best outcome of this project for me is that people see the value in taking portraits of each other as we are; without over-preparing and without ‘after-effects’ like Photoshop and soft filters. There is, surprisingly, an inner healing in the authenticity of this approach, that we discover when we see ourselves just the way we are”.

Adamson has been in talks about exhibiting his project outdoors. “Of course, my personal ambition would be to have my work exhibited in an art gallery. However, not all the people captured in these photographs would be likely to visit a gallery. So, I would prefer this work to be displayed somewhere in public, in a street exhibition perhaps, to give something back to the people of my hometown but getting permission from the local council can be problematic.”

At the time of publication, six giant posters on hoardings advertising the exhibition have so far been put up in the town centre. The rest of the images will be hosted in the Chapel Arts Gallery and in various bars and cafés around the town.

DENISE KLINK – Editor (LFI) Leica Fotografie International

Interview first published in LFI December 2018